People die. This is an unfortunate fact that we don’t like to think about, especially young people. And it’s generally relatively young people who are building websites and advising clients on how to build them. Whether through accident, illness or misadventure, people die every day. Even if none of those get you, old age eventually will. It’s something we don’t often think about, but if you make websites for a living, like I do, it’s something we should be thinking about, because our sites have to deal with it.

Lets look at things another way. Say someone in your family dies. Your brother or sister, son or daughter. Or a good friend, a friend of the family. They use the internet, they’ve got e-mail, a Facebook account and an old page on MySpace. You know about computers, so you’re asked to sort it out – to let their friends know what’s happened. You’re asked to sort it out, so what now?

If you die in the UK, your next of kin is given a death certificate. This is an official document notifying that a particular individual has died. To close bank accounts, sort out council tax, utility bills and credit accounts, you use the certificate to show a person has really died. This sort of paperwork is not a pleasant thing to deal with when you’re grieving for a loved one, but at least all the organisations you’re dealing with have policies and procedures to follow. What about websites?

E-mail

Lets take it that you don’t have the password to their e-mail. If you have, that will make everything much easier as you can use the ‘forgotten password’ facility most sites have to get access to online accounts.

If their e-mail is provided by their ISP, you may be able to call them to the get the username and password either provided over the phone or sent out by post. Then you can login to their account. Depending on the set up you’ll either be able to read all of their mail or just new items, but you’ve got access.

If they used webmail, such as Yahoo, Hotmail or Gmail, you’ll start hitting problems. I looked for the policies of the top three webmail providers, which takes quite a bit of searching and I eventually had to contact Yahoo Mail and Hotmail to ask for their policy. This would be very awkward for next of kin at such a distressing time.

Yahoo Mail – Yahoo won’t give you access to someone else’s e-mail, saying it breaks the data protection act. They didn’t say if they’ll shut down accounts or not and it took them about four weeks to respond to my inquiry.

Hotmail (free version) – Will delete all e-mail when no-one logs in for 120 days, and may delete an account if no one logs in for over a year. No reply to my inquiry yet (over a month later.)

Gmail – May delete the account after nine months of no-one logging in. They may give you access to the account if you send a copy of an e-mail that was sent to you from the account, and a copy of the death certificate or a power of attorney document. This information is available in their help centre, and wasn’t too difficult to find.

So, if your friend was with one of the top three webmail providers, you’d better hope they were with Gmail if you want access to their account. And you really need access to their e-mail because without it, you’re not going to be able to access any of their other sites.

Social Networking Sites

As mentioned before, your hypothetical friend had accounts on Facebook and MySpace. If you have access to their e-mail, you can use the ‘forgotten password’ facility on these sites to gain access to their accounts and friends lists.

What if you don’t have access to their e-mail?

MySpace – will not pass over access to an account to the next of kin as this would break their Terms and Conditions. However, if presented with an obituary or death certificate they will shut down or leave the account up so friends can leave comments.

Facebook – had the easiest to find policy, which is in it’s Terms. When told of a death, they will keep an account open for ‘a period of time’ to allow others to post comments on to the profile. This is a ‘memorialized’ state, and the comments the person has left on other pages will only be visible to the owner of the photo or original thread.

Apparently they used to close down accounts, but changed this policy after the Virginia Tech shootings, after which many friends of the pupils who had died wanted to leave comments in a format they were used to communicating over.

Bebo – I tried to find their policy and used their contact form, but haven’t heard anything back yet (it’s been over a month.)

Twitter – I wasn’t confident about getting an answer from Twitter, who are more of a loose shared commenting system than a full on social network, and were struggling to keep their service running at the time so probably have bigger issues than their policies on members who die. They use Get Satisfaction as a support forum and I haven’t had a response to my question on there yet.

If you don’t have access to the person’s e-mail, you won’t be able to access their social network accounts. If you tell the network about the death, they may be able to tell the person’s friends by changing the status of their account, or you may need to leave a comment on the account yourself via your own account on the network.

Issues

The social networks have a problem, in the case of a member dying, they need to satisfy both the wishes of the next of kin and family, and those of their friends on the network.

Frankly, this is a no-win situation for the site. People grieve in different ways, some people will want the person’s profile taken down, others will want it to stay up, forever.

If a profile stays up, is that good or bad? Do people want a constant reminder of the loss of a loved one? Their profile and comments will always look fresh, keep up to date with the latest site design, their profile picture never ages. Will this prevent us from properly moving on and coping with the death of a loved one?

What would ‘unfriend’ing a dead friend or relative mean to someone who is grieving and doesn’t want to see a reminder of them in their friend list?

Websites like MySpace and Facebook aren’t going anywhere, they are massive businesses which are worth a fortune and currently have tens of millions of active users. Even if social networking becomes less popular, they will still have a massive user base. If they do not remove accounts of deceased members, will they eventually fill up with a mountain of old users? Will it be like Hotmail of a few years back, where a future ‘Paul Silver’ won’t be able to sign up as ‘paulsilver’, but can only get ‘paulsilver1434′ because I got the first ‘paulsilver’ account when the site launched in 2008 and lots more Paul Silvers have signed up since. When I search for friends, will I mainly find deceased users whose profiles are acting as shrines to history?

Looking at this from another direction, we have a fantastic opportunity here. In the past, history has been fleeting. Conversations disappeared as soon as they were spoken. Letters may or may not get kept in family archives, but would not get passed on to anyone else. Currently, discovering the thoughts of everyday people from 200, 300, 1000, 2000 years ago would be a absolute delight to historians. We have the opportunity to save those conversations and thoughts, and keep them alive to become future history.

Maybe most contact in MySpace or Facebook seems facile, a forwarded joke here, some sarcasm about a night in the pub there. Within the muck there’s brass, but we’re not best placed to judge what’s what, because our history hasn’t happened yet. What would it be like if you could look back at your great-grandparents, and see the initial flirty comments made about each others photos, or see the photo that their friend Jack took on their phone in the pub when they first happened to meet with friends, and is still there in perfect condition 120 years later?

With the right sort of organisation, we can make an archive that can serve to help people in the future understand our time, and all the time after us, in a relatively cheap way. I’m hoping to write some more about this in the near future, but this is getting slightly off the point of this post.

A final issue I’d like to raise is domain names. Many sites use e-mail addresses as logins. I know I’ve made many that do this – it’s an easy way to get a login that’s unique for each member, and it’s easy for people to remember. However, long-term the problem with domains is that they’re rented, rather than bought. I currently own a few domains, including paulsilver.co.uk. At some point, if I don’t renew it or after I die, someone else will own paulsilver.co.uk. Lets face it, their name will probably be Paul Silver and their e-mail address paul@paulsilver.co.uk

Presuming this, that person will find it very easy to get access to lots of sites I’m registered with, because I use that address. If they try to register with that address, they’ll be told they’ve registered before, and then they can use the ‘forgotten password’ facility to get a password for the site. Suddenly, they’re me on the site. They can change my profile, delete old messages, see friends lists if it’s that sort of site, and so on.

Tentative conclusions

After a member dies, social networks should have a human keep an eye on the comments on their profile, but keep the profile active for this purpose – basically, copying what Facebook do. They may want to look at a way of limiting the visible content, depending on the wishes of the next of kin.

Sites should have a public policy on what to do when a member dies and it should be easy to find, and have a contact that’s simple to find. This is a very difficult time for the next of kin, and digging around for details will just make the situation harder for them.

Sites should look at having an extra contact for people when registering. This would effectively be a next of kin for the site. This would give them another trusted person who would be allowed access to the account, or at least friends lists, if the user dies.

Potentially there should be a time limit on what a user can change if they don’t log in for a protracted length of time. Their profile and comments could be archived to an uneditable status, so if it’s actually a new user coming to the site that happens to have the same e-mail address, they can come in to the site as a new user, but not have the ability to change an archived version of the original account.

I talked about this at BarCamp Brighton 3 and Mark Ng suggested that OpenID could run a service to let sites know of users dying, as they are plugged in to a growing number of sites for as a login system (also suggested here). Alternatively he suggested a ‘DeathAuth’ system as a kind of official notification that sites could plug in to. During the discussion we agreed there would need to be some sort of official paperwork involved in the process so erroneous authorisations could not be sent out.

Thanks

Thanks to the people at Tuttle Brighton, Brighton Farm, and BarCamp Brighton 3 for discussing this topic with me, especially as it’s quite morbid in parts.

Carl Jeffrey owns the domain Deathbook and is talking about using it to push social sites to think about these issues more thoroughly, I wish him all the best with that.

Thanks to you for getting through this massive post, I hope it’s stirred up some interesting thoughts. Please comment with your views.

[Update, Feb 2009: Apologies to everyone who commented when this was first posted, I made a mess of the database that stored my posts and the comments in and couldn’t recover them. This is a restored version of the post from before it was posted.]

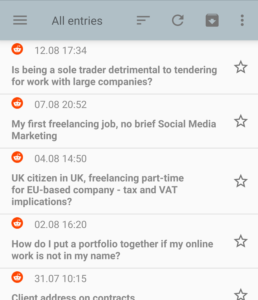

The one that has worked well is the bluntly titled RSS Reader, previously “Simple RSS Reader.” I have it set to check for updates every half an hour and it has worked great. Now, soon after a post is made I get a notification on my phone that one is waiting, pressing that opens RSS Reader and from there I can press through to the website, or just open BaconReader, my preferred app for reading Reddit, and go to that section as normal.

The one that has worked well is the bluntly titled RSS Reader, previously “Simple RSS Reader.” I have it set to check for updates every half an hour and it has worked great. Now, soon after a post is made I get a notification on my phone that one is waiting, pressing that opens RSS Reader and from there I can press through to the website, or just open BaconReader, my preferred app for reading Reddit, and go to that section as normal.